Stroke Education

Education about Aphasia and Stroke

Start at 11:29 and stop at 16:57 for the story of Elder Schenk. This happened while we were there. There was no way anyone ever thought that he would be able to live, let alone, live a productive life. But did live and he is living a productive life.

Hand Exercises

Hand Exercises

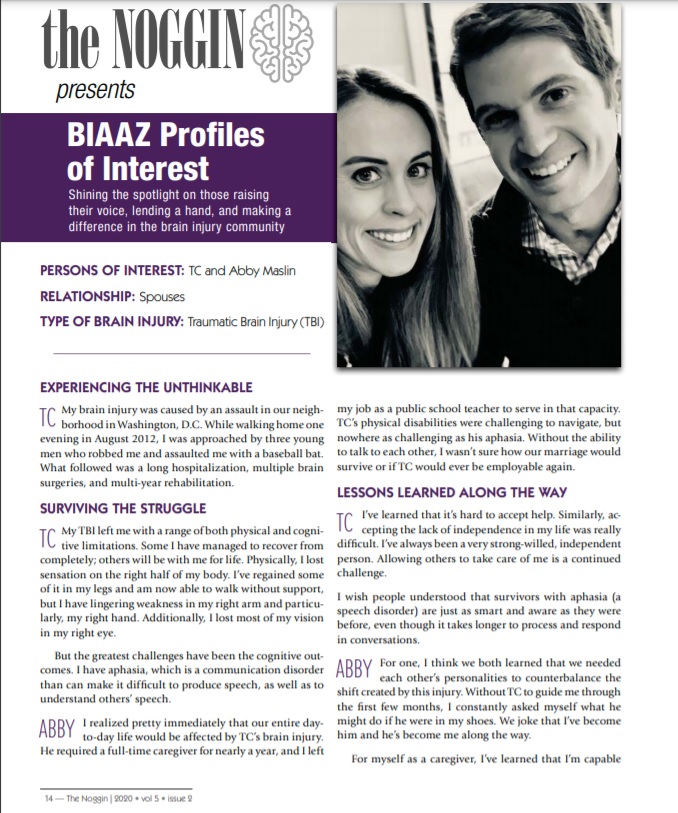

Arizona Mans Recovery

Understanding Aphasia Is the Most Important Part of Recovery

Caregivers may not fully grasp what’s involved with aphasia therapy (and how long it may take), which is why it’s crucial they know what they’re dealing with.

Two years ago, after a major stroke to the left side of his brain, Bill Forester, then 51, underwent emergency surgery to insert five stents into one of his carotid arteries. His wife, Lori Forester, remembers the aftermath as though it were yesterday.

Lori Forester had never heard the word “aphasia” before her husband Bill’s diagnosis.

“The doctors described the stroke as ‘massive,’ showed me an image of the left side of his brain, and said Bill would have difficulty communicating indefinitely,” Lori says. “They used the words ‘severe and expressive aphasia.’ I had never heard the word ‘aphasia’ before, and I was terrified.” Her worst fears were confirmed when Bill awoke after surgery. “He tried to form words, but all that came out were one-syllable stammers,” Lori recalls.

Broca’s area (a), in the frontal lobe, is important for language production. Wernicke’s area (b), in the back of the temporal lobe, aids comprehension.

Aphasia—a condition that involves difficulty in producing or understanding words and language and may include problems with reading and writing—often results from damage to certain areas on the left side of the brain where language is produced and decoded. This damage is predominantly caused by strokes—which occur when blood flow to any part of the brain is interrupted—but also can be caused by head trauma and brain tumors.

Aphasia and Stroke

“When patients who have experienced a left-brain stroke suddenly find out they can no longer speak, or speak only haltingly, it’s a dramatic situation,” says neurologist Steven Z. Rapcsak, M.D., a member of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) who specializes in language disorders, including aphasia. He is also a professor of neurology at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “In many cases, they have the thoughts and know what they’re trying to express, but they just don’t have the words,” he says.

To understand aphasia, it helps to understand a simple geography of the left side of the brain. In the frontal lobe is Broca’s area, which plays an important role in language production. Wernicke’s area, in the back of the temporal lobe, plays an important role in comprehension. A person will experience loss of function associated with the area that the stroke has damaged most, says Dr. Rapcsak. However, he adds, many strokes affect both Broca’s and Wernicke’s area, which leads to severe deficits in both language production and comprehension.

Neurologists often describe patients as having either “fluent” aphasia—when speech is produced easily, but the words chosen are often inaccurate—or “non-fluent” aphasia—when speech is slow or halting, labored, and sometimes slurred.

Understanding Aphasia Is the Most Important Part of Recovery Page 2

Of course, any serious communication deficit can be heartbreaking. “Humans are social creatures, and if they can’t communicate, they become isolated,” says Dr. Rapcsak.

The severity of a patient’s aphasia depends on how much of the left brain’s language centers the stroke has damaged. “The more massive the stroke to the language areas, the less healthy brain tissue there is to pick up the function of the damaged areas,” says Dr. Rapcsak. “The initial severity of the language deficit is a very important predictor of recovery,” says Dr. Rapcsak, adding that the patient’s age is also a factor. “An older brain has less capacity to bounce back.”

Although neurologists can determine the size and location of a stroke by looking at an image of the brain and suggest a possible course of recovery to the family, they often defer to speech-language pathologists (also known as speech therapists) to restore the communication abilities of people with aphasia.

“Post-stroke, it’s important for families to know that their neurologist is not abandoning the patient,” says Irene Katzan, M.D., M.S., a neurologist at the Cerebrovascular Center at Cleveland Clinic and a member of the AAN. “Neurologists generally feel the speech therapist is the most appropriate person to manage and treat aphasia—a team approach is best.”

Ideally, speech therapy begins while the post-stroke patient is in the hospital and then continues at an in-patient rehabilitation facility. But there’s no cookbook recipe, according to Karen Riedel, a speech-language pathologist and director of the speech-language pathology department at Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine at the New York University Langone Medical Center. “It’s complicated,” she says. “It depends on the patient, how capable he is of participating and how well he understands the condition.”

The course of treatment is not always easy. “It’s often very tough for people with aphasia to work with speech therapists because the treatment inevitably reminds patients of what they no longer can do,” says Dr. Rapcsak. “Language function that was once simple now requires effort and concentration, which can lead to frustration and depression.” In fact, many people with aphasia go through a stage of recovery in which they use profanity to express their agitation.

The mantra of discouraged patients tends to be, “I know it in here”—as they point to their heads—”but I just can’t get it out,” says Riedel. That’s why one of the best things caregivers can do for their loved ones with aphasia is to motivate them to speak as much as possible at home.

Understanding Aphasia Is the Most Important Part of Recovery Page 3

The Emotional Impact

Before Bill’s stroke, life was different for the Foresters, who live in Bay Village, a suburb of Cleveland, OH. Bill had enjoyed careers that required extensive speaking. He was an assistant-director analyst at an agency within the U.S. Department of Labor as well as an adjunct professor who taught business and real estate at a local college. Like Lori, Bill was also a licensed real estate agent. As a person with aphasia, all those activities—which helped define him—were suddenly impossible. In fact, Forester was unable to speak, recognize letters of the alphabet, or write.

“When someone has aphasia, the tools that empower them—those we use to communicate, especially speaking—are gone or defective, so you can imagine how this affects family dynamics,” says Martha Taylor Sarno, a speech pathology expert and research professor at Rusk Institute.

Before Bill Forester had aphasia, he and Lori loved informal debating. Now, she says, “Our talk is utilitarian. It’s ‘survival’ talk as opposed to philosophical conversations.” Forester’s condition also has affected their children. “Our son used to rely on Bill’s input on how to fix things, like the car,” says Lori. “But that fatherly advice went away when Bill couldn’t speak.”

“Customizing treatment according to the patient’s background is essential,” says Riedel. “It’s so important to know what the person’s verbal abilities were before the stroke. A lawyer who defended people in court, where every word counts, may have different issues than a person who, pre-stroke, did not speak much professionally,” Riedel says.

Family members may not realize the ramifications of aphasia, she observes, which is why family education—to help family members know what they’re confronting—is crucial. For example, notes Riedel, members of the household may not realize that people with aphasia may have trouble understanding what’s being said, even though it seems as though they do. When there’s no response, it’s typical for family members to mistake their loved one’s silence for stubbornness or confusion, she notes.

“Also, for some people, their speaking ability means a lot to them psychologically,” says Riedel. “So when they’re suddenly dependent on others because they can’t talk, they feel they can no longer control their life.” Many people with aphasia experience depression as a result.

Home Work

After six weeks as an inpatient in both hospital and rehabilitation settings, Bill Forester was determined to supplement his three-times-a-week speech therapy sessions at Lakewood Hospital, which is part of Cleveland Clinic, with an informal but intensive home-based strategy. The stroke had wiped out his ability to speak and use grammar. And although he could read and comprehend sentences, he had lost the ability to recognize individual letters of the alphabet.

Through their church, the family found two retired teachers who came to his home and re-taught him the alphabet. Many friends and neighbors spent time communicating with him.

It took eight months for Forester to utter the simple request, “Give me a glass of water.”

“Caregivers may not realize that most patients will improve with effort,” says Dr. Rapcsak, who concedes progress is often measured over weeks or months. “During this time, it’s critical to provide stimulation at home to supplement what a therapist does during formal therapy sessions.”

For Riedel, “stimulation” is simple: “Never stop talking to your loved ones. Keep including them in conversation,” she says. “It’s important to encourage—and expect—responses.”

Forester’s wife, Lori, believes that the absence of stimulation at home for people with aphasia undoes progress made in formal speech-therapy sessions. Attending informal group support sessions outside the home—such as aphasia support groups at a senior center or at faith-based organizations—is also beneficial. “Participating in groups is important,” says Riedel. “People with aphasia play a tremendous role for each other in these groups and even become mentors for each other. The participants in the four different aphasia groups we have at Rusk are bonded like brothers and sisters.” Many caregivers form support groups as well.

Understanding Aphasia Is the Most Important Part of Recovery Page 4

Stay Optimistic

Despite the frustration and depression that aphasia can bring, there’s reason for optimism. As recently as two decades ago, the professional belief was that one year after a stroke, a person with aphasia could expect no further improvement. Now, many experts believe that improvements can be substantial and meaningful—not only in terms of test scores but also quality of life—over a longer period of time.

“Optimism is certainly justified,” says Dr. Rapcsak. “Most people with aphasia make improvements over time.” He adds that many people who start out with mild aphasia recover fully. But even those people who do not recover their former language skills can find ways of expressing themselves, such as through art, music, and gesture.

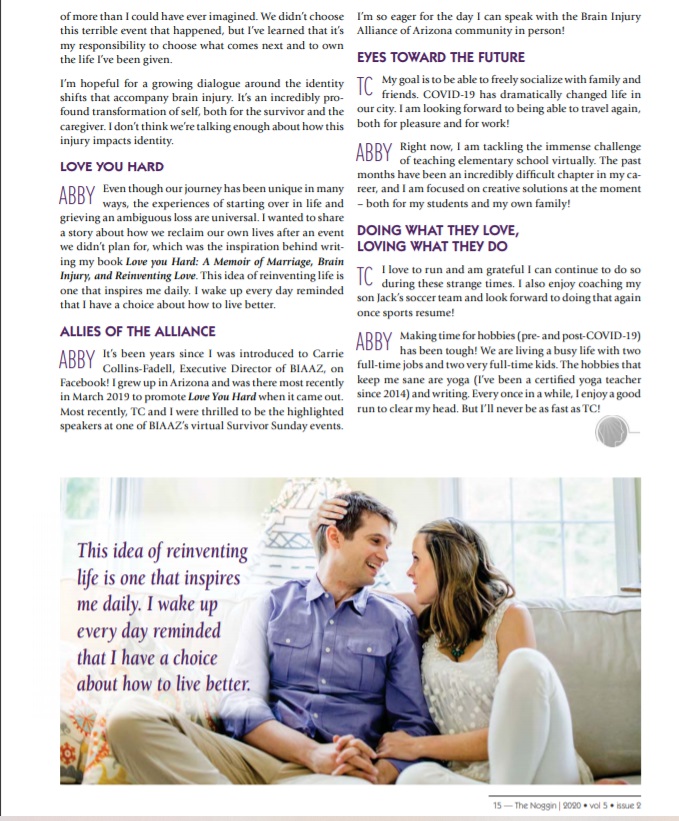

Perhaps the most reliable words of encouragement come from people who’ve successfully weathered the storm.

“Don’t believe everything you’re told by the professionals,” says Lori Forester, who recalls that her husband’s neurologist was the only doctor optimistic about Bill recovering his communication skills. Bill Forester’s determination—coupled with help from his family, friends, and volunteers—guided his extraordinary progress.

Today, two years after his stroke, he can speak in sentences, is regaining his vocabulary, and can write words and letters. He even helped create Reset, a stroke-support group that meets once a month at Lakewood that he monitors. “Doctors can’t believe my progress,” Forester says. “They ask me, ‘How can this be?’ But from the beginning, I knew I could do it. There is a light at the end of the tunnel.”

If there’s one piece of advice that Lori can share with caregivers, it’s this: “Don’t let a family member with aphasia give up,” she says. “If the patient loses hope, there’s not a lot the caregiver can do.” To illustrate her point, she says that one doctor recently told her that it’s a wonder her husband is even able to speak at all. “It’s been two years since the beginning of his aphasia and he’s still making significant progress,” she says. “Bill and I realize anything is possible.”

Practical Tips

People with aphasia certainly benefit from attending speech-therapy sessions. But what they and their caregivers do beyond the scope of those sessions can greatly improve communication and comprehension. Lori Forester—whose husband Bill Forester has made huge post-stroke strides in regaining his ability to speak, recognize letters of the alphabet, relearn grammar, and write—shares the following tips:

GET SOCIAL. Let friends make speech therapy part of the daily routine. “When Bill goes to his favorite cafe, the counter people wait until he speaks his order, even though they know how he likes his coffee,” Lori says. “It’s a friendly way to make sure people with aphasia continue to use even limited speech on a daily basis.” Sometimes a specific request by the caregiver to shop owners for this type of interaction can start the ball rolling.

GET APPS. After a stroke, damage to the brain’s language center may make it impossible for patients to physically form letters and words. Among the huge selection of iPhone applications (“apps”) that can help people with aphasia are those that display images of the mouth as it creates different letters and words. Other apps include useful words and phrases.

GET ELEMENTARY. Pull out those grade books you’ve stored in the attic. They often show, using directional arrows, how to write alphabet letters—a skill that many people with aphasia forget. Bill’s grandchildren shared their books with him, Lori says.

Finding Help After Rehab

For many people with aphasia and their loved ones, regaining speech and communication skills is accompanied by another equally daunting concern: finding treatment when the patient’s formal speech therapy ends—either because health benefits run out or because the patient is officially discharged from treatment. In some cases, community-based organizations can provide assistance.